“Etymology” is the study of the origin of words and phrases and how their meanings have changed throughout history. Etymology is important for many reasons. But, for writers, it helps establish authenticity and believability and sets the scene in your fiction story.

Problems arise when writers use a word or phrase in a scene that takes place before people actually started saying it in real life.

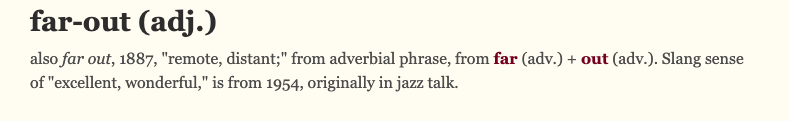

Think about a novel set during the Plague. A person approaches someone wearing one of those spooky, pointy beak masks and proclaims, “That’s some far-out headwear!” Unless that character is a time traveler, the dialogue doesn’t fit. There’s an incongruence because “far-out” originated in the jazz scene in the 1950s, not with everyday Europeans of the 1300s.

This example is, of course, pretty obvious. Most cases of a word or phrase being used before it actually entered the lexicon are subtle and easy to miss. For example, in a book I edited recently, I spotted a slang term that people didn’t start to use until nine years after the book takes place. That’s not a lot of time in the grand scheme of things, but it was enough to make the dialogue feel off and inauthentic.

When everything else in a scene (clothing, cultural references, etc.) fits with the time setting, then there is a word that’s out of its era, it sticks out. Small details like this can make or break a scene. Gather enough that are off their mark, and they can make or break the whole book.

How to check etymology

I always recommend using the Online Etymology Dictionary. It’s a quick, easy-to-use, and vast resource. Here’s its entry for “far-out,” as an example:

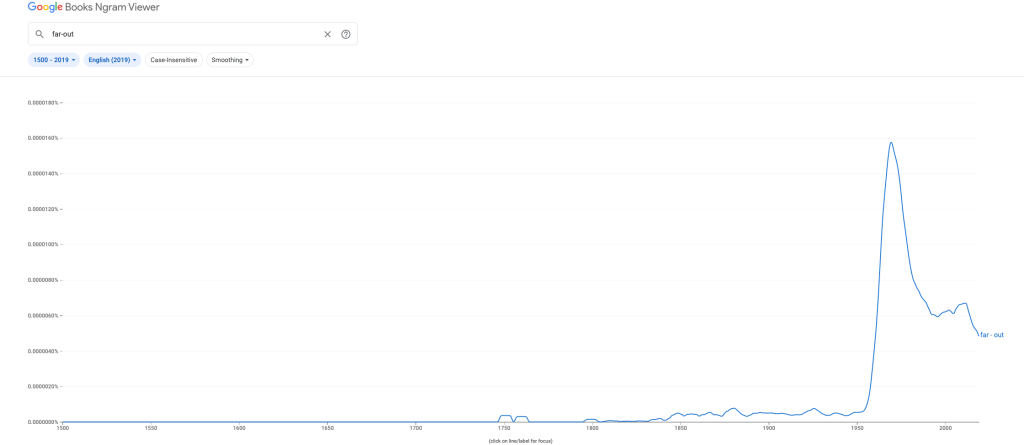

Another quick-and-easy tool is Google Ngram. Type in a word or phrase, and it will search texts and show you when it became popular. Below is what the ngram search for “far-out” looks like. Unfortunately, it only goes back to 1500, so if people were using “far-out” during the Plague, it wouldn’t show it. However, it should work for most of your purposes.

Remember: As you write, you will focus on the words you use. But also focus on when those words arose. This is just as important as other details of your scenes to establish authenticity.

Erin Servais is the founder of Dot and Dash, LLC, an author-services company focusing on women writers and offering a range of editing, coaching, and social media packages.

Sign up for the Dot and Dash newsletter to get writing tips and tricks and exclusive deals.

Follow Dot and Dash on social media.

Twitter: @GrammarParty

Instagram: @dot_and_dash_llc

Facebook: facebook.com/dotanddashllc

Pinterest: www.pinterest.com/dotanddashllc